One way to think of your college essay is as the heart of your application—as in, it helps an admissions officer see who you are, what you value, and what you bring to their campus and community.

And before we talk you through how to write your college essay, we want to acknowledge something fairly strange about this process: namely, that this is a kind of writing that you’ve maybe never been asked to do before.

In that sense, college essays are a bizarre bait-and-switch—in high school, you’re taught a few different ways to write (e.g., maybe some historical analysis, or how to analyze literature, or creative writing), and then to apply to college, you’re asked to write something fairly different (or maybe completely different) from any of the things you’ve been asked to write in high school.

So first we’ll talk you through

and then we’ll walk you step-by-step through how to write an essay that can help you stand out in the application process.

This is your main essay. Your application centerpiece. The part of your application you’re likely to spend the most time on.

Assuming you’re applying via the Common App (here’s our how-to guide for that), the personal statement is likely to be 500-650 words long (so about a page) and many of the colleges you’re applying to will require it. (If you’re applying to the UCs, you’ll need to write some totally different essays .)

What’s a college essay’s purpose?

Jennifer Blask, Executive Director for International Admissions at the University of Rochester, puts it beautifully: “So much of the college application is a recounting of things past—past grades, old classes, activities the student has participated in over several years. The essay is a chance for the student to share who they are now and what they will bring to our campus communities.”

Basically, college admission officers are looking for three takeaways in your college essay:

That really depends on a lot of factors, but two of the biggest are the schools you’re applying to, and your academic profile. Here’s one way to think of the importance of essays:

Essays are less important if

Essays are more important if

To illustrate further—CEG’s Tom Campbell, who used to be an Assistant Dean of Admissions at Pomona , puts it this way: around 80% of the applicants to Pomona in a given year when he worked there were academically admissible. Meaning at schools like Pomona (with its 7ish% acceptance rate), grades and test scores don’t really get you in—they just get your foot in the door.

And an important thing to understand on that last note: if you get rejected from the “highly rejective” schools, it will tend to have a lot more to do with things like institutional priorities —some things in this process are out of your control.

Below are the five exercises I have every student complete before I meet with them:

I recommend recording all the content from your exercises in one document to keep things neat. If you’ve been working as you go, you’ve already completed these, so make sure to do this step now. You can use our downloadable Google doc with these exercises if you’d like.

At the start of the essay process, I ask students two questions:

Because here’s an important qualifier:

I mention this now because, in my experience, many students are under the impression that they have to write about challenges—that it’s either expected, or that it’s somehow better to do so.

I’ve seen many, many incredible essays—ones that got students into every school you’re hoping to get into—that had no central challenge.

If your answer is “Maybe … ?” because you’re not sure what qualifies as a challenge, it’s useful to think of challenges as being on a spectrum.

On the weaker end of the spectrum would be things like getting a bad grade or not making X sports team. On the strong end of the spectrum would be things like escaping war. Being extremely shy but being responsible for translating for your family might be around a 3 or 4 out of 10. (Check this out if you want to read more about college essay topics to maybe avoid.)

It’s possible to use Narrative Structure to write about a challenge anywhere on the spectrum, but it’s much, much harder to write an outstanding essay about a weaker challenge.

Sometimes students pick the hardest challenge they’ve been through and try to make it sound worse than it actually was. Beware of pushing yourself to write about a challenge merely because you think these types of essays are inherently “better.” Focusing myopically on one experience can sideline other brilliant and beautiful elements of your character.

If you’re still uncertain, don’t worry. I’ll help you decide what to focus on. But, for the sake of this blog post, answer those first two questions with a gut-level response.

| 1. Challenges? | Yes/No |

| 2. Vision for your future? | Yes/No |

In the sections that follow, I’ll introduce you to two structures: Narrative Structure, which works well for describing challenges, and Montage Structure, which works well for essays that aren’t about challenges.

Heads-up: Some students who have faced challenges find after reading that they prefer Montage Structure to Narrative Structure. Or vice versa. If you’re uncertain which approach is best for you, I generally recommend experimenting with montage first; you can always go back and play with narrative.

A montage is, simply put, a series of moments or story events connected by a common thematic thread.

Well-known examples from movies include “training” montages, like those from Mulan, Rocky, or Footloose, or the “falling in love” montage from most romantic comedies. Or remember the opening to the Pixar movie Up? In just a few minutes, we learn the entire history of Carl and Ellie’s relationship. One purpose is to communicate a lot of information fast. Another is to allow you to share a lot of different kinds of information, as the example essay below shows.

Narrative Structure vs. Montage Structure explained in two sentences:

In Narrative Structure, story events connect chronologically.

In Montage Structure, story events connect thematically.

Here’s a metaphor to illustrate a montage approach:

Imagine that each different part of you is a bead and that a select few will show up in your essay. They’re not the kind of beads you’d find on a store-bought bracelet; they’re more like the hand-painted beads on a bracelet your little brother made for you.

The theme of your essay is the thread that connects your beads.

You can find a thread in many, many different ways. One way we’ve seen students find great montage threads is by using the 5 Things Exercise. I’ll get detailed on this a little bit later, but essentially, are there 5 thematically connected things that thread together different experiences/moments/events in your life? For example, are there 5 T-shirts you collected, or 5 homes or identities, or 5 entries in your Happiness Spreadsheet.

And to clarify, your essay may end up using only 4 of the 5 things. Or maybe 8. But 5 is a nice number to aim for initially.

Note the huge range of possible essay threads. To illustrate, here are some different “thread” examples that have worked well:

All of these threads stemmed from the brainstorming exercises in this post.

We’ll look at an example essay in a minute, but before we do, a word (well, a bunch of words) on how to build a stronger montage (and the basic concept here also applies to building stronger narratives).

Imagine you’re interviewing for a position as a fashion designer, and your interviewer asks you what qualities make you right for this position. Oh, and heads-up: That imaginary interviewer has already interviewed a hundred people today, so you’d best not roll up with, “because I’ve always loved clothes” or “because fashion helps me express my creativity.” Why shouldn’t you say those things? Because that’s what everyone says.

Many students are the same in their personal statements—they name cliché qualities/skills/values and don’t push their reflections much further.

Why is this a bad idea?

Let me frame it this way:

Important: I’m not saying you should pick a weird topic/thread just so it’ll help you stand out more on your essay. Be honest. But consider this: The more common your topic is . the more uncommon your connections need to be if you want to stand out.

For example, tons of students write doctor/lawyer/engineer essays; if you want to stand out, you need to say a few things that others don’t tend to say.

How do you figure out what to say? By making uncommon connections.

They’re the key to a stand-out essay.

The following two-part exercise will help you do this.

2-minute exercise: Start with the cliché version of your essay.

What would the cliché version of your essay focus on?

If you’re writing a “Why I want to be an engineer” essay, for example, what 3-5 common “engineering” values might other students have mentioned in connection with engineering? Use the Values Exercise for ideas.

Collaboration? Efficiency? Hands-on work? Probably yes to all three.

Once you’ve spent 2 minutes thinking up some common/cliché values, move onto the next step.

8-Minute Exercise: Brainstorm uncommon connections.

For example, if your thread is “food” (which can lead to great essays, but is also a really common topic), push yourself beyond the common value of “health” and strive for unexpected values. How has cooking taught you about “accountability,” for example, or “social change”? Why do this? We’ve already read the essay on how cooking helped the author become more aware of their health. An essay on how cooking allowed the author to become more accountable or socially aware would be less common.

In a minute, we’ll look at the “Laptop Stickers” essay. One thing that author discusses is activism. A typical “activist” essay might discuss public speaking or how the author learned to find their voice. A stand-out essay would go further, demonstrating, say, how a sense of humor supports activism. Perhaps it would describe a childhood community that prioritized culture-creation over culture-consumption, reflecting on how these experiences shaped the author’s political views.

And before you beg me for an “uncommon values” resource, I implore you to use your brilliant brain to dream up these connections. Plus, you aren’t looking for uncommon values in general; you’re looking for values uncommonly associated with your topic/thread.

Don’t get me wrong . I’m not saying you shouldn’t list any common values, since some common values may be an important part of your story! In fact, the great essay examples throughout this book sometimes make use of common connections. I’m simply encouraging you to go beyond the obvious.

Also note that a somewhat-common lesson (e.g., “I found my voice”) can still appear in a stand-out essay. But if you choose this path, you’ll likely need to use either an uncommon structure or next-level craft to create a stand-out essay.

Where can you find ideas for uncommon qualities/skills/values?

Here are four places:

This is basically a huge list of qualities/skills/values that could serve you in a future career.

Go to www.onetonline.org and use the “occupation quick search” feature to search for your career. Once you do, a huge list will appear containing knowledge, skills, and abilities needed for your career. This is one of my favorite resources for this exercise.

3. School websites

Go to a college's website and click on a major or group of majors that interest you. Sometimes they’ll briefly summarize a major in terms of what skills it’ll impart or what jobs it might lead to. Students are often surprised to discover how broadly major-related skills can apply.

Ask 3 people in this profession what unexpected qualities, values, or skills prepared them for their careers. Please don’t simply use their answers as your own; allow their replies to inspire your brainstorming process.

Once you’ve got a list of, say, 7-10 qualities, move on to the next step.

Common personal statement topics include extracurricular activities (sports or musical instruments), service trips to foreign countries (aka the “mission trip” essay where the author realizes their privilege), sports injuries, family illnesses, deaths, divorce, the “meta” essay (e.g., “As I sit down to write my college essays, I think about. ”), or someone who inspired you (common mistake: This usually ends up being more about them than you).

While I won’t say you should never write about these topics, if you do decide to write about one of these topics, the degree of difficulty goes way up. What do I mean? Essentially, you have to be one of the best “soccer” essays or “mission trip” essays among the hundreds the admission officer has likely read (and depending on the school, maybe the hundreds they’ve read this year). So it makes it much more difficult to stand out.

How do you stand out? A cliché is all in how you tell the story. So, if you do choose a common topic, work to make uncommon connections (i.e., offer unexpected narrative turns or connections to values), provide uncommon insights (i.e., say stuff we don’t expect you to say) or uncommon language (i.e., phrase things in a way we haven’t heard before).

Or explore a different topic. You are infinitely complex and imaginative.

My laptop is like a passport. It is plastered with stickers all over the outside, inside, and bottom. Each sticker is a stamp, representing a place I’ve been, a passion I’ve pursued, or community I’ve belonged to. These stickers make for an untraditional first impression at a meeting or presentation, but it’s one I’m proud of. Let me take you on a quick tour:

“We ,” bottom left corner. Art has been a constant for me for as long as I can remember. Today my primary engagement with art is through design. I’ve spent entire weekends designing websites and social media graphics for my companies. Design means more to me than just branding and marketing; it gives me the opportunity to experiment with texture, perspective, and contrast, helping me refine my professional style.

“Common Threads,” bottom right corner. A rectangular black and red sticker displaying the theme of the 2017 TEDxYouth@Austin event. For years I’ve been interested in the street artists and musicians in downtown Austin who are so unapologetically themselves. As a result, I’ve become more open-minded and appreciative of unconventional lifestyles. TED gives me the opportunity to help other youth understand new perspectives, by exposing them to the diversity of Austin where culture is created, not just consumed.

Poop emoji, middle right. My 13-year-old brother often sends his messages with the poop emoji ‘echo effect,’ so whenever I open a new message from him, hundreds of poops elegantly cascade across my screen. He brings out my goofy side, but also helps me think rationally when I am overwhelmed. We don’t have the typical “I hate you, don’t talk to me” siblinghood (although occasionally it would be nice to get away from him); we’re each other’s best friends. Or at least he’s mine.

“Lol ur not Harry Styles,” upper left corner. Bought in seventh grade and transferred from my old laptop, this sticker is torn but persevering with layers of tape. Despite conveying my fangirl-y infatuation with Harry Styles’ boyband, One Direction, for me Styles embodies an artist-activist who uses his privilege for the betterment of society. As a $42K donor to the Time’s Up Legal Defense Fund, a hair donor to the Little Princess Trust, and promoter of LGBTQ+ equality, he has motivated me to be a more public activist instead of internalizing my beliefs.

“Catapult,” middle right. This is the logo of a startup incubator where I launched my first company, Threading Twine. I learned that business can provide others access to fundamental human needs, such as economic empowerment of minorities and education. In my career, I hope to be a corporate advocate for the empowerment of women, creating large-scale impact and deconstructing institutional boundaries that obstruct women from working in high-level positions. Working as a women’s rights activist will allow me to engage in creating lasting movements for equality, rather than contributing to a cycle that elevates the stances of wealthy individuals.

“Thank God it’s Monday,” sneakily nestled in the upper right corner. Although I attempt to love all my stickers equally (haha), this is one of my favorites. I always want my association with work to be positive.

And there are many others, including the horizontal, yellow stripes of the Human Rights Campaign; “The Team,” a sticker from the Model G20 Economics Summit where I collaborated with youth from around the globe; and stickers from “Kode with Klossy,” a community of girls working to promote women’s involvement in underrepresented fields.

When my computer dies (hopefully not for another few years), it will be like my passport expiring. It’ll be difficult leaving these moments and memories behind, but I probably won’t want these stickers in my 20s anyways (except Harry Styles, that’s never leaving). My next set of stickers will reveal my next set of aspirations. They hold the key to future paths I will navigate, knowledge I will gain, and connections I will make.

Cool, huh? And see what I mean about how you can write a strong personal statement without focusing on challenges you’ve faced?

Going back to that “thread and beads” metaphor with the “My Laptop Sticker” essay:

The outline that got her there

Here’s the outline for the “My Laptop Stickers” essay. Notice how each bullet point discusses a value or values, connected to different experiences via her thread, and sets up the insights she could explore. (Insight, though, is the toughest part of the writing process, and will probably take the most revision, so it’s fine if you don’t have great insights in an outline or first draft. But you’ll want to get to them by your final draft.)

She found this thread essentially by using The Five Things Exercise in conjunction with the other brainstorming exercises.

Thread = Laptop Stickers

Okay, so if you’re on board so far, here’s what you need:

First, let’s talk about .

How to generate lots of ‘stuff’ to write about (aka the beads for your bracelet)

Complete all the brainstorming exercises.

Already did that? Great! Move on!

Didn’t do that? Go back, complete the exercises, and then .

Case study: How to find a theme for your personal statement (aka the thread that connects the beads of your bracelet)

Let’s look at an example of how I helped one student find her essay thread, then I’ll offer you some exercises to help you find your own.

First, take a look at this student’s Essence Objects and 21 Details:

My Essence Objects

My 21 Details

How this author found her thematic thread

When I met with this student for the first time, I began asking questions about her objects and details: “What’s up with the Bojangle’s Iced Tea? What’s meaningful to you about the Governor’s School East lanyard? Tell me about your relationship to dance . ”

We were thread-finding . searching for an invisible connective [something] that would allow her to talk about different parts of her life.

Heads-up: Some people are really good at this—counselors are often great at this—while some folks have a more difficult time. Good news: When you practice the skill of thread-finding, you can become better at it rather quickly.

You should also know that sometimes it takes minutes to find a thread and sometimes it can take weeks. With this student, it took less than an hour.

I noticed in our conversation that she kept coming back to things that made her feel comfortable. She also repeated the word “home” several times. When I pointed this out, she asked me, “Do you think I could use ‘home’ as a thread for my essay?”

“I think you could,” I said.

Read her essay below, then I’ll share more about how you can find your own thematic thread.

As I enter the double doors, the smell of freshly rolled biscuits hits me almost instantly. I trace the fan blades as they swing above me, emitting a low, repetitive hum resembling a faint melody. After bringing our usual order, the “Tailgate Special,” to the table, my father begins discussing the recent performance of Apple stock with my mother, myself, and my older eleven year old sister. Bojangle’s, a Southern establishment well known for its fried chicken and reliable fast food, is my family’s Friday night restaurant, often accompanied by trips to Eva Perry, the nearby library. With one hand on my breaded chicken and the other on Nancy Drew: Mystery of Crocodile Island, I can barely sit still as the thriller unfolds. They’re imprisoned! Reptiles! Not the enemy’s boat! As I delve into the narrative with a sip of sweet tea, I feel at home.

“Five, six, seven, eight!” As I shout the counts, nineteen dancers grab and begin to spin the tassels attached to their swords while walking heel-to-toe to the next formation of the classical Chinese sword dance. A glance at my notebook reveals a collection of worn pages covered with meticulously planned formations, counts, and movements. Through sharing videos of my performances with my relatives or discovering and choreographing the nuances of certain regional dances and their reflection on the region’s distinct culture, I deepen my relationship with my parents, heritage, and community. When I step on stage, the hours I’ve spent choreographing, creating poses, teaching, and polishing are all worthwhile, and the stage becomes my home.

Set temperature. Calibrate. Integrate. Analyze. Set temperature. Calibrate. Integrate. Analyze. This pulse mimics the beating of my heart, a subtle rhythm that persists each day I come into the lab. Whether I am working under the fume hood with platinum nanoparticles, manipulating raw integration data, or spraying a thin platinum film over pieces of copper, it is in Lab 304 in Hudson Hall that I first feel the distinct sensation, and I’m home. After spending several weeks attempting to synthesize platinum nanoparticles with a diameter between 10 and 16 nm, I finally achieve nanoparticles with a diameter of 14.6 nm after carefully monitoring the sulfuric acid bath. That unmistakable tingling sensation dances up my arm as I scribble into my notebook: I am overcome with a feeling of unbridled joy.

Styled in a t-shirt, shorts, and a worn, dark green lanyard, I sprint across the quad from the elective ‘Speaking Arabic through the Rassias Method’ to ‘Knitting Nirvana’. This afternoon is just one of many at Governor’s School East, where I have been transformed from a high school student into a philosopher, a thinker, and an avid learner. While I attend GS at Meredith College for Natural Science, the lessons learned and experiences gained extend far beyond physics concepts, serial dilutions, and toxicity. I learn to trust myself to have difficult yet necessary conversations about the political and economic climate. Governor’s School breeds a culture of inclusivity and multidimensionality, and I am transformed from “girl who is hardworking” or “science girl” to someone who indulges in the sciences, debates about psychology and the economy, and loves to swing and salsa dance. As I form a slip knot and cast on, I’m at home.

My home is a dynamic and eclectic entity. Although I’ve lived in the same house in Cary, North Carolina for 10 years, I have found and carved homes and communities that are filled with and enriched by tradition, artists, researchers, and intellectuals. While I may not always live within a 5 mile radius of a Bojangle’s or in close proximity to Lab 304, learning to become a more perceptive daughter and sister, to share the beauty of my heritage, and to take risks and redefine scientific and personal expectations will continue to impact my sense of home.

But here’s the question I get most often about this technique: How do I find my thematic thread?

1. The “Bead-Making” Exercise (5-8 min.)

In the example above, we started with the beads, and then we searched for a thread. This exercise asks you to start with the thread of something you know well and then create the beads. Here’s how it works:

Step 1: On a blank sheet of paper, make a list of five or six things you know a lot about.

For example, I know a lot about …

If you can only think of 3 or 4, that’s okay.

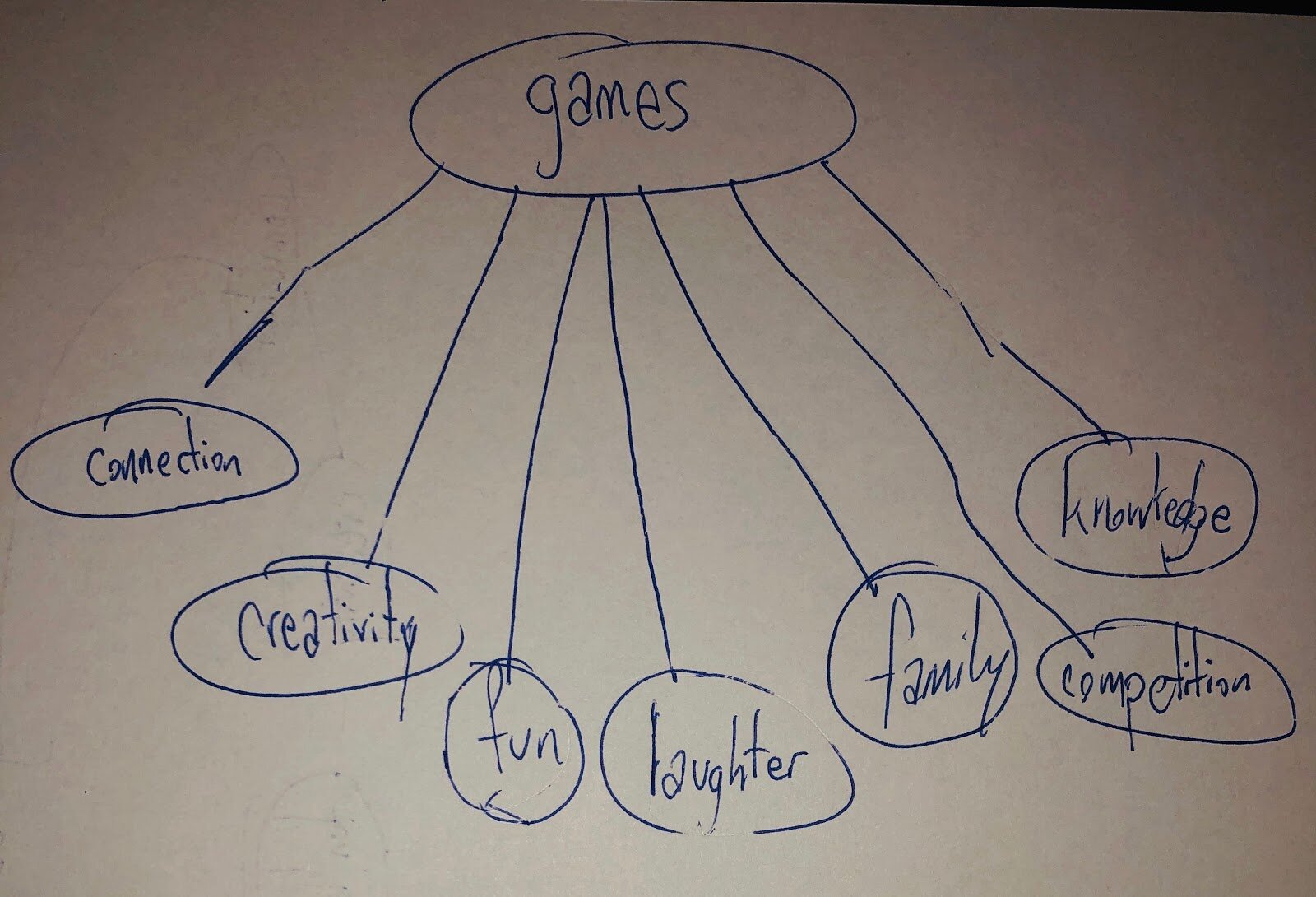

Step 2: Pick one of the things you wrote down, flip your paper over, and write it at the top of your paper, like this:

This is your thread, or a potential thread.

Step 3: Underneath what you wrote down, name 5-6 values you could connect to this. These will serve as the beads of your essay. You can even draw a thread connecting your beads, if you want, like this:

Step 4: For each value, write down a specific example, memory, image, or essence object that connects to that value. Example:

My thread: Games

My beads: Connection, creativity, fun/laughter, family, competition, knowledge

Here are my examples/memories/images/essence objects:

This is an actual brainstorm I did using this exercise.

And, as I write these things down, I notice a theme of youth/old age emerging. Games have changed for me as I’ve gotten older. Note that I couldn’t come up with something for the last one, “knowledge,” which is fine.

The point is this: If you know a thing well, odds are good you’ll be able to make a lot of connections to your values. And if you can find specific examples for each value, that can make for interesting paragraphs in your personal statement.

If you’re willing to spend a few more minutes, ask “so what?” of each example to see if a specific insight emerges.

And, in case you want a formula for what I’m describing, here you go:

Once you’ve written down the values and at least one example (e.g., a memory, image, essence object) for each bead, see if you have enough content for an essay.

Still haven’t found your theme? Here are .

2. The “Five Things” Exercise

(Special thanks to my colleague, Dori Middlebrook, for this one.)

I mentioned this when we first started talking about Montage Structure. Similar to the “bead-making” exercise above, you identify the thread first and then develop the beads.

Step 1: Write down 5 similar things that are meaningful to you in different ways.

Step 2: Begin by simply naming the 5 different items.

Step 3: Add physical details so we can visualize each one.

Step 4: Add more details. Maybe tell a story for each.

Step 5: Expand on each description further and start to connect the ideas to develop them into an essay draft.

3. Thread-finding with a partner

Grab someone who knows you well (e.g., a counselor, friend, family member). Share all your brainstorming content with them and ask them to mirror back to you what they’re seeing. It can be helpful if they use reflective language and ask lots of questions. An example of a reflective observation is: “I’m hearing that ‘building’ has been pretty important in your life … is that right?” You’re hunting together for a thematic thread—something that might connect different parts of your life and self.

4. Thread-finding with photographs

Pick 10 of your favorite photos or social media posts and write a short paragraph on each one. Why’d you pick these photos? What do they say about you? Then ask yourself, “What are some things these photos have in common?” Bonus points: Can you find one thing that connects all of them?

5. Reading lots of montage example essays that work

You’ll find some here, here, and here. While you may be tempted to steal those thematic threads, don’t. Try finding your own. Have the courage to be original. You can do it.

Q: How do I work in extracurricular activities in a tasteful way (so it doesn’t seem like I’m bragging)?

A: Some counselors caution, with good reason, against naming extracurricular activities/experiences in your personal statement. (It can feel redundant with your Activities List.) You actually can mention them, just make sure you do so in context of your essay’s theme. Take another look at the eighth paragraph of the “My Laptop Stickers” essay above, for example:

And there are many [other stickers], including the horizontal, yellow stripes of the Human Rights Campaign; “The Team,” a sticker from the Model G20 Economics Summit where I collaborated with youth from around the globe; and stickers from “Kode with Klossy,” a community of girls working to promote women’s involvement in underrepresented fields.

A description of these extracurricular activities may have sounded like a laundry list of the author’s accomplishments. But because she’s naming other stickers (which connects them to the essay’s thematic thread), she basically gets to name-drop those activities while showing other parts of her life. Nice.

One more way to emphasize a value is to combine or disguise it with humor. Example: “Nothing teaches patience (and how to tie shoes really fast) like trying to wrangle 30 first-graders by yourself for 10 hours per week,” or “I’ve worked three jobs, but I’ve never had to take more crap from my bosses than I did this past summer while working at my local veterinarian’s office.”

In each of these examples, the little bit of humor covers the brag. Each is basically pointing out that the author had to work a lot and it wasn’t always fun. No need to push this humor thing, though. Essays don’t need to be funny to be relatable, and if the joke doesn’t come naturally, it might come across as trying too hard.

Q: How do I transition between examples so my essay “flows” well?

A: The transitions are the toughest part of this essay type. Fine-tuning them will take some time, so be patient. One exercise I love is called Revising Your Essay in 5 Steps, and it basically works like this:

This is a great way to figure out the “bones” (i.e., structure) of your essay.

Q: What am I looking for again?

A: You’re looking for two things:

Your theme could be something mundane (like your desk) or something everyone can relate to (like the concept of home), but make sure that it is elastic (i.e. can connect to many different parts of you) and visual, as storytelling made richer with images.

Each of the values creates an island of your personality and a paragraph for your essay.

Montage step-by-step recap:

Q: This is hard! I’m not finding it yet and I want to give up. What should I do?

A: Don’t give up! Remember: be patient. This takes time. If you need inspiration, or assurance that you’re on the right track, check out Elizabeth Gilbert’s TED Talk, “Your Elusive Creative Genius.”

All right, moving on.

If you answered “yes” to both questions at the beginning of this guide, I recommend exploring Narrative Structure. I’ll explain this in more detail below.

My favorite content-generating exercise for Narrative Structure is the Feelings and Needs Exercise. It takes about 20 minutes (but do feel free to take longer—more time brainstorming and outlining leads to better, faster writing). Here’s how it works:

Time: 15-20 minutes

If you haven’t completed the exercise, please do it now.

(And this is a dramatic pause before I tell you the coolest thing about what you just did.)

You may notice that your completed Feelings and Needs chart maps out a potential structure for your personal statement. If you’re not seeing it, try turning your paper so that the challenges are at the top of your page and the effects are below them.

Voila. A rough outline for a narrative essay.

To clarify, this isn’t a perfect way to outline an essay. You may not want to spend an entire paragraph describing your feelings, for example, or you may choose to describe your needs in just one sentence. And now that you see how it frames the story, you may want to expand on certain columns. However, the sideways Feelings and Needs chart can help you think about how the chronology of your experiences might translate into a personal statement.

Here’s an essay that one student wrote after completing this exercise:

The narrow alleys of Mardan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan where I spent the first 7 years of my life were infiltrated with the stench of blood and helplessness. I grew up with Geo news channel, with graphic images of amputated limbs and the lifeless corpses of uncles, neighbors, and friends. I grew up with hurried visits to the bazaar, my grandmother in her veil and five-year-old me, outrunning spontaneous bomb blasts. On the open rooftop of our home, where the hustle and bustle of the city were loudest, I grew up listening to calls to prayer, funeral announcements, gunshots. I grew up in the aftermath of 9/11, confused.

Like the faint scent of mustard oil in my hair, the war followed me to the United States. Here, I was the villain, responsible for causing pain. In the streets, in school, and in Baba’s taxi cab, my family and I were equated with the same Taliban who had pillaged our neighborhood and preyed on our loved ones.

War followed me to freshman year of high school when I wanted more than anything to start new and check off to-dos in my bullet journal. Every time news of a terror attack spread, I could hear the whispers, visualize the stares. Instead of mourning victims of horrible crimes, I felt personally responsible, only capable of focusing on my guilt. The war had manifested itself in my racing thoughts and bitten nails when I decided that I couldn’t, and wouldn’t, let it win.

A mission to uncover parts of me that I’d buried in the war gave birth to a persona: Sher Khan, the tiger king, my radio name. As media head at my high school, I spend most mornings mastering the art of speaking and writing lighthearted puns into serious announcements. Laughter, I’ve learned, is one of the oldest forms of healing, a survival tactic necessary in war, and peace too.

During sophomore year, I found myself in International Human Rights, a summer course at Cornell University that I attended through a local scholarship. I went into class eager to learn about laws that protect freedom and came out knowledgeable about ratified conventions, The International Court of Justice, and the repercussions of the Srebrenica massacre. To apply our newfound insight, three of my classmates and I founded our own organization dedicated to youth activism and spreading awareness about human rights violations: Fight for Human Rights. Today, we have seven state chapters led by students across the U.S and a chapter in Turkey too. Although I take pride in being Editor of the Golden State’s chapter, I enjoy having written articles about topics that aren’t limited to violations within California. Addressing and acknowledging social issues everywhere is the first step to preventing war.

Earlier this year, through KQED, a Bay Area broadcasting network, I was involved in a youth takeover program, and I co-hosted a Friday news segment about the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals policy, the travel ban, and the vaping epidemic. Within a few weeks, my panel and interview were accessible worldwide, watched by my peers in school, and family thousands of miles away in Pakistan. Although the idea of being so vulnerable initially made me nervous, I soon realized that this vulnerability was essential to my growth.

I never fully escaped war; it’s evident in the chills that run down my spine whenever an untimely call reaches us from family members in Pakistan and in the funerals still playing on Geo News. But I’m working towards a war-free life, internally and externally, for me and the individuals who can share in my experiences, for my family, and for the forgotten Pashtun tribes from which I hail. For now, I have everything to be grateful for. War has taught me to recognize the power of representation, to find courage in vulnerability, and best of all, to celebrate humor.

Fun fact: This essay was written by a student in one of my online courses who, as she shared this version with me, called it a “super rough draft.”

I wish my super rough drafts were this good.

I share this essay with you not only because it’s a super awesome essay that was inspired by the Feelings and Needs Exercise, but also because it offers a beautiful example of what I call the .

You can think of a narrative essay as having three basic sections: Challenges + Effects; What I Did About It; What I Learned. Your word count will be pretty evenly split between the three, so for a 650-word personal statement, 200ish each.

To get a little more nuanced, within those three basic sections, a narrative often has a few specific story beats. There are plenty of narratives that employ different elements (for example, collectivist societies often tell stories in which there isn’t one central main character/hero, but it seems hard to write a college personal statement that way, since you’re the focus here). You’ve seen these beats before—most Hollywood films use elements of this structure, for example.

For example, take a look at “The Birth of Sher Khan” essay above.

Notice that roughly the first third focuses on the challenges she faced and the effects of those challenges.

Roughly the next third focuses on actions she took regarding those challenges. (Though she also sprinkles in lessons and insight here.)

The final third contains lessons and insights she learned through those actions, reflecting on how her experiences have shaped her. (Again, with the caveat that What She Did and What She Learned are somewhat interwoven, and yours likely will be as well. But the middle third is more heavily focused on actions, and the final third more heavily focused on insight.)

And within those three sections, notice the beats of her story: Status Quo, The Inciting Incident, Raising the Stakes/Rising Action, Moment of Truth, New Status Quo.

How does the Feelings and Needs Exercise map onto those sections?

At the risk of stating the blatantly obvious, The Challenges and Effects columns of the Feelings and Needs Exercise … are the Challenges + Effects portion of your essay. Same with What I Did and What I Learned.

The details in your Feelings and Needs columns can be spread throughout the essay. And it’s important to note that it’s useful to discuss some of your feelings and needs directly, but some will be implied.

For example, here’s the Feelings and Needs Exercise map of the “Sher Khan” essay. And I know I just mentioned this, but I want you to notice something that’s so important, I’m writing it in bold: The author doesn’t explicitly name every single effect, feeling, or need in her essay. Why not? First, she’s working within a 650-word limit. Second, she makes room for her reader’s inferences, which can often make a story more powerful. Take a look:

Cool. Here’s another narrative example:

At six years old, I stood locked away in the restroom. I held tightly to a tube of toothpaste because I’d been sent to brush my teeth to distract me from the commotion. Regardless, I knew what was happening: my dad was being put under arrest for domestic abuse. He’d hurt my mom physically and mentally, and my brother Jose and I had shared the mental strain. It’s what had to be done.

Living without a father meant money was tight, mom worked two jobs, and my brother and I took care of each other when she worked. For a brief period of time the quality of our lives slowly started to improve as our soon-to-be step-dad became an integral part of our family. He paid attention to the needs of my mom, my brother, and me. But our prosperity was short-lived as my step dad’s chronic alcoholism became more and more recurrent. When I was eight, my younger brother Fernando’s birth complicated things even further. As my step-dad slipped away, my mom continued working, and Fernando’s care was left to Jose and me. I cooked, Jose cleaned, I dressed Fernando, Jose put him to bed. We did what we had to do.

As undocumented immigrants and with little to no family around us, we had to rely on each other. Fearing that any disclosure of our status would risk deportation, we kept to ourselves when dealing with any financial and medical issues. I avoided going on certain school trips, and at times I was discouraged to even meet new people. I felt isolated and at times disillusioned; my grades started to slip.

Over time, however, I grew determined to improve the quality of life for my family and myself.

Without a father figure to teach me the things a father could, I became my own teacher. I learned how to fix a bike, how to swim, and even how to talk to girls. I became resourceful, fixing shoes with strips of duct tape, and I even found a job to help pay bills. I became as independent as I could to lessen the time and money mom had to spend raising me.

I also worked to apply myself constructively in other ways. I worked hard and took my grades from Bs and Cs to consecutive straight A’s. I shattered my school’s 1ooM breaststroke record, and learned how to play the clarinet, saxophone, and the oboe. Plus, I not only became the first student in my school to pass the AP Physics 1 exam, I’m currently pioneering my school’s first AP Physics 2 course ever.

These changes inspired me to help others. I became president of the California Scholarship Federation, providing students with information to prepare them for college, while creating opportunities for my peers to play a bigger part in our community. I began tutoring kids, teens, and adults on a variety of subjects ranging from basic English to home improvement and even Calculus. As the captain of the water polo and swim team I’ve led practices crafted to individually push my comrades to their limits, and I’ve counseled friends through circumstances similar to mine. I’ve done tons, and I can finally say I’m proud of that.

But I’m excited to say that there’s so much I have yet to do. I haven’t danced the tango, solved a Rubix Cube, explored how perpetual motion might fuel space exploration, or seen the World Trade Center. And I have yet to see the person that Fernando will become.

I’ll do as much as I can from now on. Not because I have to. Because I choose to.

There’s so much to love about this essay.

Here’s a behind-the-scenes look at how the author wrote this essay so you can figure out how to write yours:

First, the author brainstormed the content of his essay using the Feelings and Needs Exercise.

Did you spot the elements of that exercise? If not, here they are:

That’s why I love beginning with this exercise. With just 15-20 minutes of focused work, you can map out your whole story.

Next, the author used Narrative Structure to give shape to his essay.

Did you spot the Narrative Structure elements? If not, here they are:

And again, notice that those fit within the framework of: